From Landscape Architect to Cemetery Founder: Q&A with Co-Founder Chris Alonso

- Lauren Robie

- Sep 17, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Oct 2, 2025

Q: How did Hope begin?

Hope Eternal Gardens began with my mother, Kena Alonso. She lived with Inclusion Body Myositis, a disease that weakened her muscles, but even as her health declined, her mind remained sharp. During those final years, it was deeply important to respect her independence - her ability to make choices about her life, her death, and her legacy. One of her last wishes was to create a natural burial cemetery for her community.

Over time, I came to see that what she imagined was more than just a resting place - it was the beginning of something that could profoundly shape Southwest Florida.

Q: What role did your mother play in shaping this vision?

My mother's background gave her the insight to imagine something this ambitious. She was a successful real estate broker, with experience developing and constructing residential projects and even a condominium in Punta Gorda Isles. For over 30 years, she and I had worked together on landscape projects, blending her creativity and business acumen with my design and construction experience as a landscape architect. She understood both the practical side of land development and the human side of creating spaces where people could live and thrive.

Just as important were her gardens. Wherever our family lived, she made a point to create both edible gardens - filled with fruit trees, vegetables, and herbs - and ornamental gardens designed simply for beauty. She composted, captured rainwater, and practiced low-maintenance, Florida-friendly gardening long before it became a common phrase. Watching her transform bare ground or turf into abundant gardens showed me how powerful it could be to design with nature in mind.

One of her last requests was that Hope should feel like a botanical garden. She loved visiting

Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota and Naples Botanical Garden, and she wanted visitors to feel the same sense of inspiration and peace. Her love of plants and her conviction that gardens could be low-maintenance and chemical-free shaped our earliest designs for Hope.

What began as fulfilling her request has grown into a mission that carries her spirit forward.

Her last garden: from turf to Florida-friendly edible garden

Left: Aerial from 2006. Right: Aerial from 2025.

Q: What were some of the challenges you faced - and how did they shape Hope?

Hope was tested from the very beginning. We needed land that met strict state requirements for cemetery licensing - at least 30 acres with paved road access. We faced failed contracts, zoning hurdles, and extensive permitting challenges. Each setback forced us to refine our ideas. What might have discouraged us instead clarified our commitment and made our design stronger.

Gardening a Forest

The biggest design breakthrough came from grappling with Kena’s wish for gardens. At first, we thought in terms of traditional botanical gardens like Selby and Naples Botanical Garden. But through our landscape architecture firm, TOPO_GRAPHIC, we were working on a report analyzing how even “low-maintenance” landscapes could fail when maintenance crews overwatered, underwatered, or replaced plants with the wrong species. Around the same time, we came across the book Overgrown: Practices between Landscape Architecture and Gardening by Julian Raxworthy, which argued that gardeners and maintenance shape landscapes as much as the original design.

It became clear: we needed a system that could sustain itself. I remembered the small forests I had planted years earlier with Miami-Dade County Parks, and I reconnected with the Miyawaki method. Looking at examples from Afforestt in India and SUGi projects in different climates, we realized that what we needed was not individual plantings, but forests. This approach required more care in the beginning, but the payoff would be long-term resilience — and it allowed families to plant something with deep emotional meaning from the very beginning.

Stormwater

Another example was stormwater. In Florida, licensed landscape architects are allowed to design and seal stormwater plans, but some agencies still require a professional engineer’s signature. I designed Hope’s stormwater system with bioswales and stormwater ponds, but we had to find an engineer willing to collaborate closely while preserving the vision. That collaboration didn’t just meet requirements — it produced a design that succeeds in filtering water, protecting wetlands, and supporting the ecological health of the site.

Hope grew stronger each time we faced an obstacle. Every challenge clarified what this place needed to be.

Q: What does being a landscape architect bring to this project?

I’m a licensed landscape architect (and also a LEED -Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design- Accredited Professional, Building Design and Construction), which means I was trained to design with ecology, people, and long-term resilience in mind. Landscape architecture is more than gardening or maintenance - it’s a licensed profession that requires years of schooling, testing, and continuing education. We design the systems that shape how people experience outdoor spaces, from stormwater to habitat to circulation.

Landscape architects rarely lead projects from conception or have a daily, hands-on approach after construction administration is complete. Typically, engineers or architects take the lead. The fact that Hope is led by a landscape architect makes it unusual in our field — and uniquely positioned to succeed.

Hope is designed as both a cemetery and a living landscape that will grow more valuable with time. That dual focus — ecological and human — is what landscape architecture makes possible.

Q: What past projects prepared you for Hope?

Every project I’ve worked on taught me something that shows up in Hope.

Northeast Library, Miami, FL

At the Northeast Library – which achieved LEED Silver certification – I led the design and implementation of the cistern, a fountain courtyard, living walls, and the restoration of the stormwater basin. What had originally been a conventional engineered grass basin was transformed into an enhanced stormwater system, integrating ecological performance with design. In addition, I coordinated and completed all LEED requirements for the project, ensuring that sustainable design goals were fully met.

Stormwater Pond: Before and After

Virginia Key & Bill Sadowski Parks, Miami, FL

While working for Miami-Dade Parks, I created forest plantings that went on to become self-sustaining habitats, using principles similar to the Miyawaki method.

Honey Hill, Miami, FL

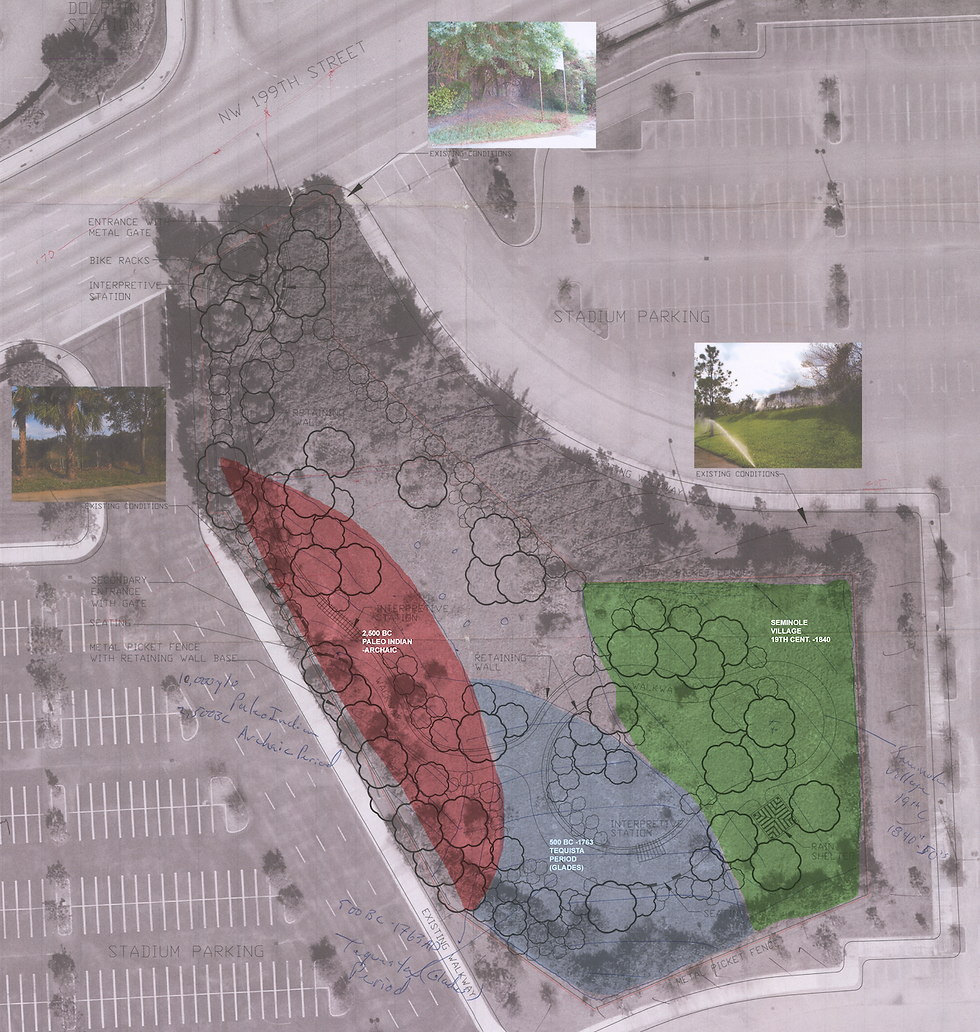

I was the landscape architect in charge of construction drawings and construction administration for Honey Hill, which preserved a sacred Tequesta burial ground. This reinforced the importance of honoring history and cultural sites in design.

Archaeologists studied this site in the 1980s during the construction of the Dolphin Stadium. Slated for destruction to make way for a parking lot, the Honey Hill site was saved by Miami-Dade County and is now an archaeological preserve and park.

The park contains interpretive signage, shelters, shade trees, and pathways that encourage a greater appreciation of the space and its history. I worked with the Miami-Dade County Archaeologist to develop plans to create an archaeological park that helps preserve and educate the public about the preexisting village and cemetery of the Tequesta. To help preserve the artifacts, the entire site had to be filled with 2 feet of soil.

Forest Hills Cemetery Art Installation, Boston, MA

Collaborating with the late Susan Child, Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects, and a pioneering figure in landscape architecture history, I helped design an art installation within this historic cemetery. It showed me how cemeteries could be places of art and cultural expression.

‘A TRANSECT’ AT FOREST HILLS CEMETERY

Artist statement by Susan Child and Chris Alonso in 2003:

”A transect is a transverse cut across an area, usually in the form of a long, continuous strip.Historically, it has been used by botanists to provide a sample area of a site’s vegetation.

We envision this transect as an artistic exploration of the Forest Hills Cemetery site.We used natural elements to draw a line traversing 1,700 feet of New England glacial terrain.This line reveals a cross-section of elements, both natural — botanic and topographic — and man-made pathways and memorial stones.

The transect is visual yet abstract. It describes physical elements as they are randomly encountered, creating a microcosm of the larger site.The long line, which is always seen only in part, suggests infinity.

The processes of change in nature will become evident as the lime disintegrates over time and is transformed into a lush, emerald green line.”

Beirut Peacekeepers Memorial Tower

I designed a landscape that would conceptually complement the memorial tower, showing how planting and site design can strengthen meaning and experience.

The landscape reinforces the duality of tragedy of the 1983 Beirut Bombing by using the circled cross as a symbol with two meanings: 1) to suggest the Beirut Bombing, and 2) to symbolize the rays of hope that radiate through the affected families and community.The Beirut Peacekeepers Memorial Tower project is the result of private/public partnership: the William R.Gaines Jr. Veterans Memorial Fund and Charlotte County, FL.

The Mount, Lenox, MA

Working on the restoration of Edith Wharton’s estate highlighted the cultural value of designed landscapes and the role that maintenance plays in preserving them. As principal of Child Associates, I worked with Susan Child to restore The Mount, Edith Wharton’s 100-year-old gardens and landscape. I worked on the construction documents for the Flower Garden and the Sunken Garden, and the planting plan for the Rock Garden. This project was featured in Landscape Architecture Magazine, September 2003.

157th Ave. Bike Trail - Miami, FL

I designed & developed construction documents and permitted plans to create a 1-mile multi-use trail, including way-finding signage, regulatory signage, and enhanced pedestrian crossing and landscaping. The plantings provide shade, while the under-story planting and wildflower mix will help reduce maintenance cost. The design also created additional linear parks where future shelters, butterfly gardens, and seating can be installed.

Q: What technology do you use at Hope?

Many cemeteries rely on pencil and paper for recordkeeping. At Hope, we’ve chosen to use state-of-the-art tools because they help families today and they create a digital archive for the future.

We use design software like Vectorworks, Lumion, Adobe Creative Suite, Civil 3D, HydroCAD, Infraworks, and Moasure to create precise drawings and immersive visuals so families can better understand what their legacy will look like. We’re also in the process of implementing webCemeteries, a leading digital platform for cemetery recordkeeping and mapping. All of these tools allow us to serve families with clarity, to collect meaningful ecological data, and to contribute to research on the benefits of natural burial and forest creation.

Doing this level of design and data collection in-house is unusual for a cemetery. It’s one more way we’re setting Hope apart and building for the long term.

Q: What is your educational background?

My path in education has always revolved around design, ecology, and the arts.

Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) – I earned my Master of Landscape Architecture at RISD, a program known for blending art, ecology, and design. My time there taught me to see landscapes not just as spaces, but as systems that shape how people live and connect with the natural world.

University of Georgia (UGA) – I received my Bachelor of Landscape Architecture at UGA, home to one of the oldest landscape architecture programs in the country. It gave me a strong foundation in both technical skills and ecological design.

UGA Cortona, Italy – Through UGA, I studied abroad in Tuscany. Seeing historic gardens, cities, and landscapes firsthand gave me a deep respect for cultural landscapes and the ways people have shaped the land for centuries.

Gwinnett Technical College – Earlier in my path, I studied horticulture and landscape design here. It was very hands-on, and it gave me practical skills with plants and site maintenance that still influence the way I design today.

Chris in Italy

Q: What does Hope represent for you now?

What began as my mother’s wish has become a reality. At first, I did this to honor her. Along the way, I discovered that Hope could be a gift to Southwest Florida and even beyond — a place where families can mourn, celebrate, and contribute to something lasting.

The personal meaning never leaves. When I design for families at Hope, it matters to me that this place allows people to feel whatever they need to feel — sorrow, love, gratitude, or something in between. It is meaningful to bring an added depth of empathy to that design work, knowing from personal experience how powerful it is when a landscape can hold the full weight of our emotions.

Hope is not only my mother’s legacy — it has become my life’s work.